The holidays are a distant memory. You have returned from the beach or your site in the mountains – from your seat at the bar, from your towel by the pool, from the depths of your summer dreaming – to a land of demands and obligations, to a time of no time at all.

Another year is underway.

You have your plans. A long list of writing tasks. A creative map and new ideas. You make that list every year and every year it defeats you. Your work is strangely hit and miss, and then the year is gone.

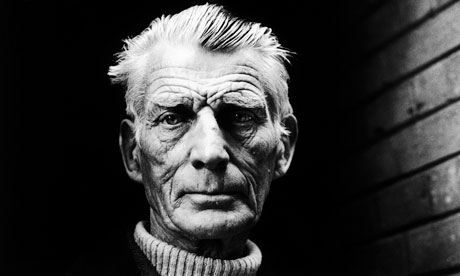

“No matter,” wrote Samuel Beckett. “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

How good is that? Failure is inevitable, but not inconsequential: whoever fails better succeeds a little more. So keep on keeping on.

Beckett did. Long before the Irish poet, playwright and novelist won the 1969 Nobel Prize for Literature, he was a solemn and solitary young man with “little talent for happiness” (his words).

In his early twenties he secured an academic post at Trinity College, Dublin, but his career lasted less than two years.

His study of Marcel Proust – the French novelist responsible for the truly novel and monumental work, In Search of Lost Time – convinced Beckett that his own time was finite, and likely to be lost in the formal habits and settled routine of the academe.

So Beckett took to the road: wandering Europe; working when he had to; writing when he could.

His first novel was rejected by countless publishers. His most famous work, Waiting for Godot (1953), took five years from page to stage; it was a critical success in Paris, but opened in London to mainly negative reviews.

He invited failure, too. Despite being a native English speaker, Beckett (pictured) wrote much of his work in French. Can you imagine a natural right-hander electing to play his tennis left-handed?

Beckett, it seems, sought in his writing the clarity and economy of expression that his second language necessarily imposed. Armed with less, and unburdened by excessive literary style or cultural baggage, Beckett had more.

You see it when – as in the case of Waiting for Godot – Beckett translates his work from French back into English:

ESTRAGON: Why don’t we hang ourselves?

VLADIMIR: With what?

ESTRAGON: You haven’t got a bit of rope?

VLADIMIR: No.

ESTRAGON: Then we can’t.

“Compact” is one word that critics use to describe Beckett’s later works; “refined” might be another.

Towards the end, Beckett wasted nothing. He wrote in small ways about big things – boredom, despair, confusion, sadness, irony, time and memory – and this, in part, is what gives his writing its greatness, its universality and enduring appeal.

Beckett’s characters live in a perpetual ‘Groundhog Day’: they stand stranded, dazed, lonely and alone in a fog that never lifts. They are bewildered, battered, bored and overwhelmed.

Absurd? Or life as we know it? Few make it through: eternally marooned, baffled and confused, it is no wonder they go in search of ropes.

But not Beckett. He worked. He wrote. He lived. And no amount of existential theory negates the fact that he showed up every day and put his pen to paper.

And you? To what this year will you bring your energy, time and imagination?

Surely the lesson of Beckett is that if nothing amounts to nothing then something amounts to something.

So make your plans. Write your lists. Set your goals and get to work.

And fail again. Fail better.

First published in the Victorian Writer magazine, March 2012

Well written piece Paul with great expression! Written back in March 2012 – but just as fresh 5 years later & still as relevant today.

Love Mum xxx

Many thanks!! xx Paul